Individual Mobility. What does it take to bring you from A to B?

From an individual’s point of view, mobility simply is the possibility to be mobile, to go from one place to another – no matter where these places are. Typical criteria to evaluate this possibility are availability, accessibility, possible destinations, time to destination, cost, safety, comfort, reliability, sustainability etc.

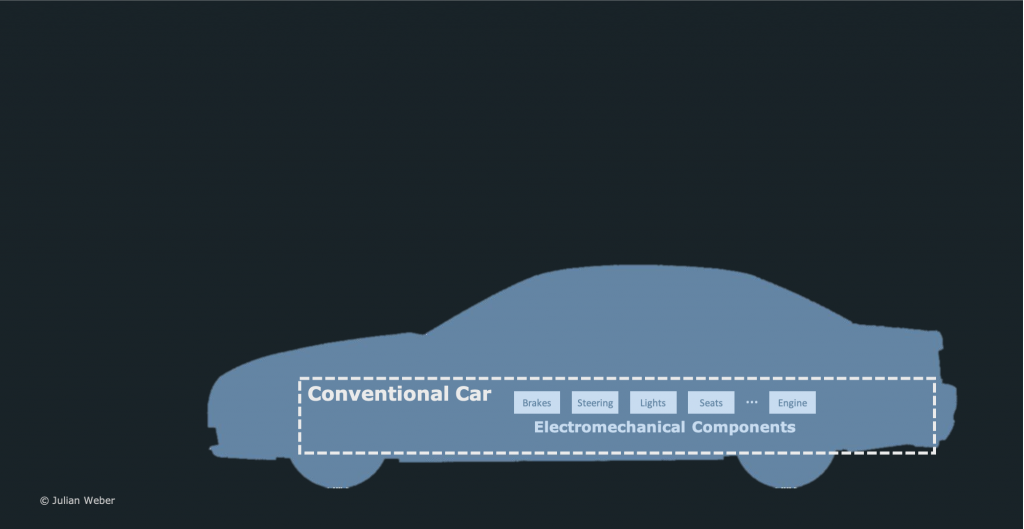

To do so, you can either walk or use a means of transport – which can be any kind of vehicle from bicycle to car, from boat to drone, from e-scooter to airplane, from subway to cable car or even horses and donkeys.

Dropping the relatively rare (and in the context of this article irrelevant) case that you employ a personal chauffer, captain or pilot and are a passenger in your own vehicle, this leaves you with two options: You must either operate your own vehicle or use one rendered to you through a mobility service – such as public transport, ride hailing, bike sharing, airplanes or whatever.

Infrastructure. What you just expect to be there.

A precondition for the proper usage of these vehicles is a functioning infrastructure. Mobility infrastructure comprises a broad bandwidth of things and services, e.g.:

- The structure the vehicle needs to operate (such as walkways, bike lanes, streets, rails, tunnels, bridges, waterways or air routes)

- Means to enter or leave the vehicle (parking spaces, parking structures, stations, ports, airports etc.)

- Traffic control elements (such as road markings, traffic signs, traffic lights, barriers, access control, traffic and parking surveillance etc.)

- Energy provision (such as fuel stations, chargers or overhead lines)

- Structures and services to maintain and repair vehicles as well as infrastructure

- Data networks (such as mobile internet access)

- Regulatory framework including legal requirements for vehicles and mobility services as well for their operation, tolls and taxes

In Short: To be mobile, you need your own vehicle or access to a mobility service. And in both cases, you depend on the availability of the appropriate infrastructure.

Collective Mobility. Unfortunately, other people want to be mobile, too.

Securing all these requirements alone would be tough enough, but as we all experience on a daily basis: How well one person can realize his or her mobility needs also depends strongly on the mobility patterns of all others. Jammed streets, overcrowded subways, limited availability of sharing vehicles, scarcity of parking spaces, local and global emission limits keep you from doing what you would do if you would be the only one out there. Why the heck must all others use this road, bus or service when I want to?

How well everyone in a given area can fulfill their mobility needs at the same time is what we call Collective Mobility. Securing and optimizing Collective Mobility is one of the primary regulatory tasks of cities, regions or countries and means nothing less than controlling the interplay of all vehicles being used, mobility services being rendered, and infrastructure being operated and maintained in a given mobility system. And we all know how rudimentary especially big cities handle this challenge today.

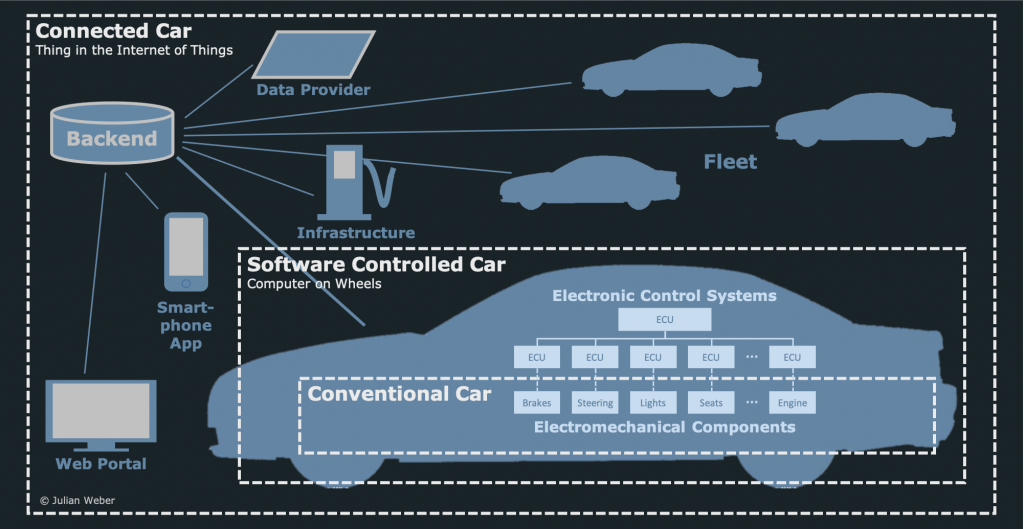

From opinions to knowledge. Big Data helps understanding.

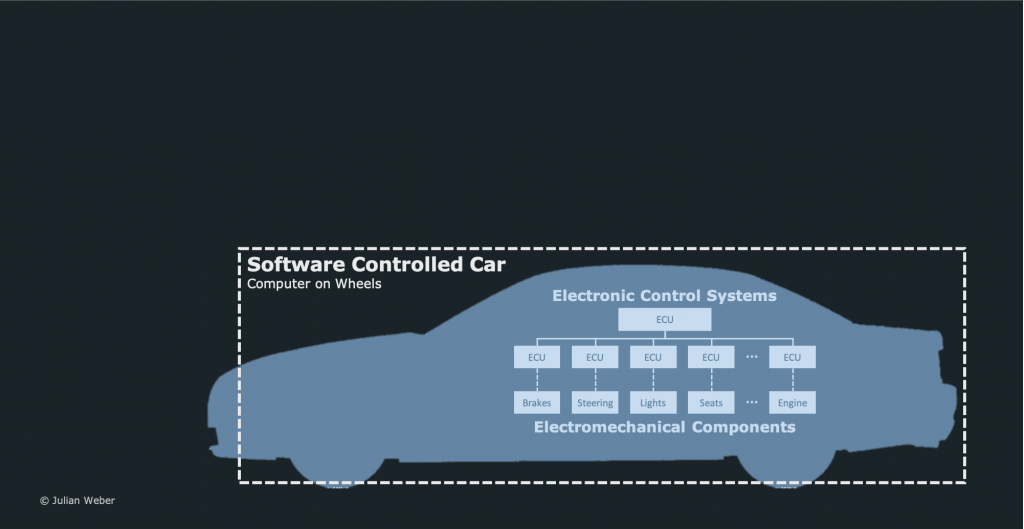

A promising strategy to improve in this endeavor is utilizing what I call the “Internet of Mobility”: Vehicles, users, infrastructure – they all are getting more and more equipped with sensors (and hence create more and more data) and become more and more connected to the internet. There’s hardly one person on the street without a smart phone, service systems share their data and most importantly the sum of connected cars out there on the roads, which – from a data analyst’s point of view – represent nothing less than a huge, densely distributed network of powerful, mobile, and somewhat over-motorized sensor clusters constantly transmitting really big data ready to be collected and analyzed.

Such data is already available und used today, but at comparably low quantity and quality, and we are only at the beginning of holistically utilizing it. To picture what you get from conventionally connected cars compared to having digital twins: Most cars out there today leave you a little sticky note at the fridge door saying, “I drove 54 kilometers today, my tank is half full, all doors are locked, and I am generally doing fine.” However, cars with state-of-the-art connectivity have you on the phone 24/7, telling you constantly about each and every feeling and perception they have.

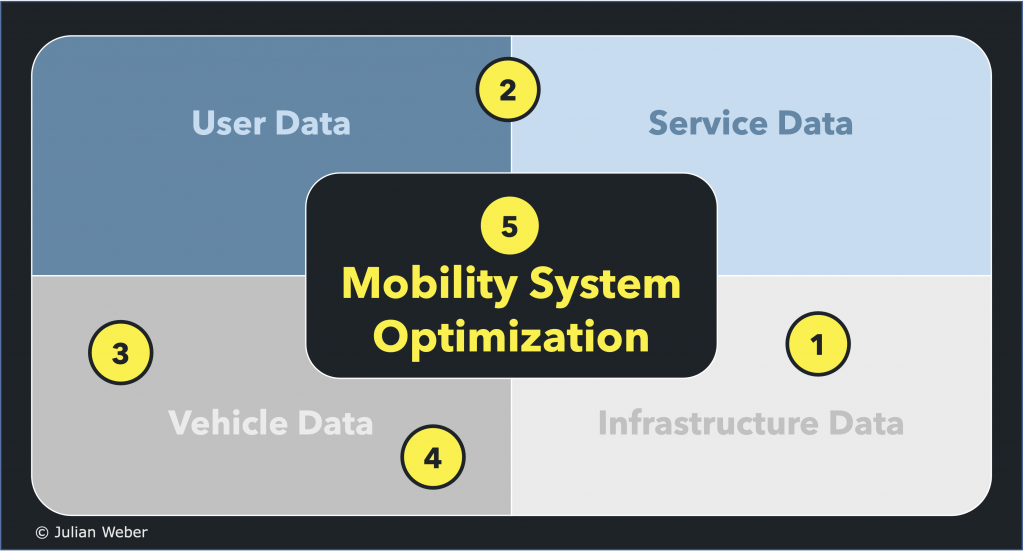

It is this increase and improvement of available data and especially the consolidated analysis of vehicle, user, and infrastructure generated data that allows the holistic optimization of mobility systems in the future. Here, I see mainly five main dimensions:

1. Improve Vehicle Operations

Real-time knowledge of infrastructure conditions and availability

- facilitates parking and fueling/charging,

- enables the early detection and even prediction of mobility-inhibiting factors such as traffic jams, potholes, slippery road surfaces or any other hazards, and

- is the basis for any kind of autonomous driving.

2. Improve Mobility Services

Time- and location-based knowledge of user behavior and service utilization allows providers to

- select the optimum vehicle and features for their service offers,

- optimize both number and distribution of the vehicles used in their sharing or ride hailing schemes (including public transport), and especially

- make mobility services as a whole more attractive (e.g., than driving your own vehicle) by optimizing the interplay between various offers (e.g., ride hailing, public transport and parking structures).

3. Improve Vehicle Condition

Real-time knowledge of all vehicles’ technical condition allows

- detection of technical problems and thus facilitation of their solving, and

- prediction of maintenance or repair needs and thus keeping vehicles smoothly running whilst avoiding breakdowns.

4. Improve Infrastructure Operations

Environmental data provided by connected cars allows

- detection and prediction of infrastructure maintenance needs (e.g., broken traffic lights, worn road markers, damaged streets, bridges, or structures),

- detection and prediction of general traffic capacity overload.

5. Improve Mobility System as a Whole

Combining and analyzing data rendered by all users, infrastructure and vehicles in a given mobility system allows the responsible authorities to

- monitor, predict and control traffic flow and emissions,

- decide targeted measures to improve the mobility system with regards comfort, safety and costs based on the received insights, and

- detect and follow up on traffic violations.

As with all other forms of digital transformation, this approach comes with a twofold challenge: Firstly, the technical realization of the data utilization cycle (generate, transfer, aggregate, analyze, act, measure). Secondly, the persuasive and convincing efforts required to get all people involved supporting this change – sometimes letting go processes they are not only used to for years but have helped to establish and thus are personally attached to.