Since Mark Zuckerberg announced in Summer 2021 that Meta-turned Facebook would now focus on establishing and expanding the metaverse, shared digital universes have become a ubiquitous megatrend, and one business report after the other promises vast opportunities offered both through creation and utilization of such digital worlds. However, distributed virtual worlds and the related business promises are all but new and – as so often – in order to critically evaluate what the future might really bring, it is worth taking a look back and see what has been already learned in the past.

Part 1: 30 Years of Hype, Disillusionment, and Lots of Learnings

The Spirit was Willing, but the Hardware was Weak

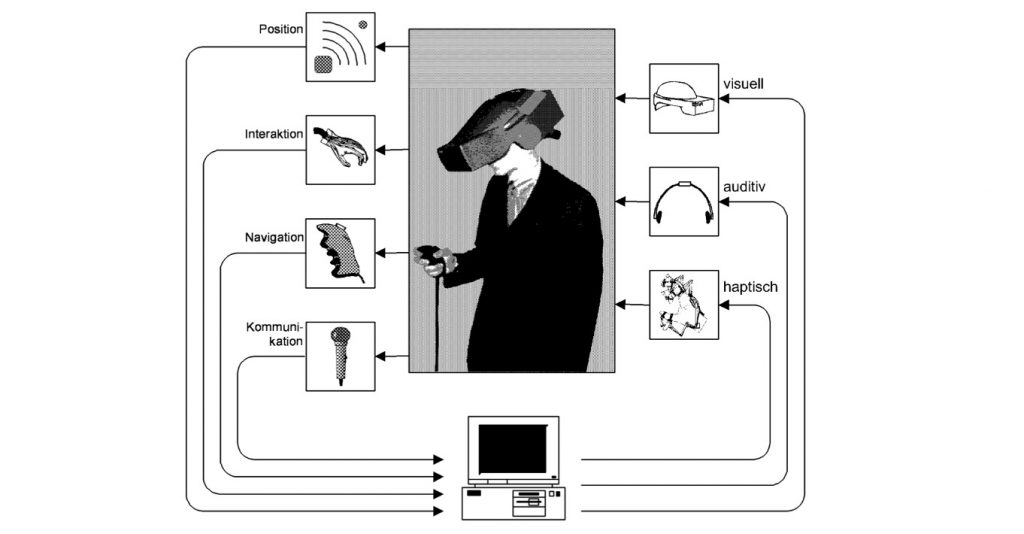

It surely was kind of directive that the first to mention and describe the idea of a shared digital world wasn’t a scientist: In his 1984 book Newromancer, SciFi author William Gibson wrote about a Cyberspace, which people could enter via various hardware interfaces in order to cooperate and interact there with each other. People from the most diverse areas were fascinated of this idea. In the following years, Virtual Reality (as the new terminus technicus was) became a real hype and I a research assistant at the School of Mechanical Engineering of Karlsruhe Technical University, where I wrote my PhD thesis on the utilization of Virtual Reality for evaluating 3D product models – an incredibly cool topic for a mechanical engineer working for a machine tooling institute.

Powerful graphic computers like the Dream Machine from Silicon Graphics, Inc. were almost unaffordable at that time, considering available research funds. Consequently, the virtual production scenarios created to facilitate the planning of real-world assembly lines were mostly represented by simple boxes. The world consisted of cuboids. Further VR equipment such as HMDs (Head Mounted Device) or Data Gloves which are necessary to immerse in the virtual world were heavy and clumsy prototypes. If you looked at the boxes in your virtual world and turned your head, it took a while until the projection on the monitors integrated in the HMD followed, which almost inevitably led to nausea after a couple of minutes. Even during a trip to England, where we visited the most renowned VR research facilities in VR, we were still staring at virtual boxes while slowly getting pale and sick.

Picture 1: Immersion with Head Mounted Display and Space Mouse 1995

But on the other hand, those technical restrictions gave place to an almost unlimited forward thinking. Intense theoretical discussions of its future potential made Virtual Reality a typical “one day, we could …” topic across all industries and research facilities. Theoretically possible applications of virtual worlds in almost any area, from architecture through cooperative 3D product design to cybersex (a topic that was covered by almost every magazine at that time and made it sometimes difficult to state that you “were in Virtual Reality”) were analyzed widely and thoroughly. Even the validity of spiritual interactions like blessings or confessions carried out in cyberspace was discussed.

Technology Goes Where the Money is. But Where is the Money?

But while what was considered serious research at that time was lacking the money to afford the appropriate hardware, VR technology grew – initially almost unnoticed – somewhere else: At the last day of the aforementioned trip to England, we visited a huge gaming center at Trocadero in London and their new VR games – and here I eventually was felt genuinely immersed in a virtual world for the first time. There were quite obviously much more funds available in gaming than in R&D or production. Alternating between envy and admiration, we looked in their hardware room filled up with the most powerful SGI computers and the best equipment I had used so far. And: In contrast to the research facilities, there were long queues of people waiting to pay five pounds and more for a few minutes of immersion into a virtual battlefield. Still, gaming was not considered a serious field of action for engineering researchers at the end of the 90es.

It was also a computer game, namely the ego-shooter game Doom, where I for the first time experienced cooperation in a shared virtual environment (even though cooperation might be a strange term for the kind of interaction you have in games like Doom). The possibility to meet and interact with other people from all over the world in a virtual room in real time was breathtaking and so much better than in all the VR environments we were used to work with.

Since then, 3D online gaming has made tremendous progress in multiple dimensions. Advanced graphic processors most notably from Invidia or AMD and VR headsets like Oculus Rift now enable highly realistic visualization of and interaction with all kinds of elements of shared virtual worlds. By playing online games like Fortnite or Minecraft, especially Generation Z is used from the very beginning to almost naturally act and interact in virtual worlds. Gaming has become not only a widespread hobby, but – as more and more people also enjoy watching other people play – for some a quite profitable profession. Ninja, then 20 years old, is said to be the first one to make 12 million dollars a year by playing Fortnite and other games. Looking up to such new role models, thousands of kids worldwide started dreaming of a career as a professional gamer – much to the dismay of their parents and a generation that had no understanding at all for this business. E-sports – as gaming is called today – has become a significant industry and is still the main driver for technological development in Virtual Reality.

What are the House Rules, if the House is not Real?

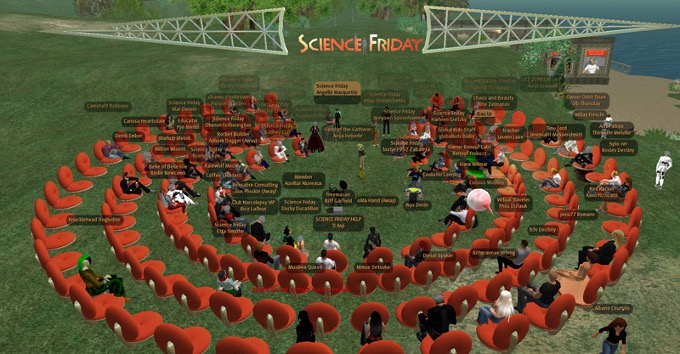

In 2003, one year before Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook went online, cooperation in shared virtual worlds made a huge step forward when US based Linden Lab started Second Life, a commercial multi-user multi-purpose 3D Environment. Represented by avatars, users from all over the world entered Second Life – first for fun, later also for research and education as well as for marketing and commerce. Schools and universities offered lessons and lectures, while companies offered their products and services. Means of payment was a first virtual currency, the Linden Dollar, that could be exchanged for real money. The first truly populated virtual universe allowing social interaction and a very basic form of commerce was born. In a nutshell, Second Life was Internet 2.0 going 3D.

Picture 2: NPR Science Friday in Second Life 2008 (Source: Wikipedia)

But while focusing on new features and increasing the number users, Linden Lab did not think too much about the related risks. Consequently, users were soon to experience that a more or less unregulated virtual world also nourished negative societal behavior patterns such as hate speech, injustice, copyright violation, spreading of lies, or general indecency. It didn’t take long until the citizens of Second Life, typically strong advocates of freedom and independence, were yawning for rules and regulations and their enforcement. Another learning with regards to legal aspects was the lack of IP protection that people and companies offering services in Second Life were facing.

Enriching Reality with Matching Virtual Worlds

While the quality and importance of purely virtual spaces had significantly grown over the years, overlaying and matching of virtual and real world never was too much in the center of attention. Though there were some industrial Augmented Reality applications, where maintenance or logistics workers got additional information to the objects they are handling projected in their glasses, but even the Google Glass introduced in 2014 and intended to widespread AR was only sold for a year.

And it was gaming again, where AR applications broke through. In 2016, millions of Pokémon Go users started wandering around the neighborhoods, virtually looking at the world through their smartphones’ cameras to see their real environment enriched by virtual items they had to catch. However, keeping an eye both on the real and the virtual world was obviously difficult, as you could see flocks of players carelessly crossing streets while looking at the display of their phone.

But what prevailed much more than matching virtual and real geometry data was the creation and utilization of digital twins, digital models representing the current state of real, connected objects in – more or less – real time. Enabled by the worldwide implementation of cloud computing, data lakes were filled with digital twins of connected equipment, machinery, appliances, cars etc. to create Production 4.0 and the Internet of Things. Even though the focus of the digital models used here today is less on 3D geometry than on technological data, they represent cooperatively used virtual worlds that make it possible to represent real objects in virtual worlds in real time.

Immersion – the Holy Grail of Virtual Reality

One – if not the first – question in debating Virtual Reality has always been whether it was really necessary to be immersed in a virtual world or whether watching it on a monitor would also qualify for “true” VR. And still today, there seems to be no clear answer. Experiencing a metaworld as realistically as possible through headsets and other hardware has advantages but also disadvantages compared to watching yourself (or more precisely your avatar) from bird‘s eye view on a display. In gaming e.g., immersion is chosen by players who just enjoy being in the middle of the virtual scenario while professional players prefer watching the battleground on large curved screens because of the better overview and faster reaction.

Spending Real Money in Unreal Worlds

Online payment for products and services rendered in the real or virtual world is quite obviously a necessary prerequisite for doing business in virtual worlds. It surely was Jeff Bezos and Amazon who boosted development of online payment technology for internet purchasing since the mid-nineties. However, it wasn’t before Second Life that inhabitants of virtual worlds could change real money in a virtual currency to purchase virtual products and get access to virtual services. Today, virtual spaces like Metaverse can rely on a plethora of payment solutions, including blockchain technologies to make business transparent and tamper-proof.

Part 2: Metaverse Today

Well, now what has changed over the years and what can we learn from the past?

First and foremost: The idea of immersing yourself in a shared virtual world, slip into a new character and personality there, and freely interact with others independently from all the restrictions the real world might impose – be it geographically, legally, societal or individually – still fascinates people, is technically possible, but – though partially implemented – still a vision.

True: There are – in addition to cooperative gaming spaces like Fortnite, Minecraft or Meta’s Horizon Worlds – generic metaverse platforms available today (most notably Decentraland, Sandbox, Cryptovoxels, Substrata or, Somnium Space), where people meet and interact, attend concerts, or engage in educational events. They pay to pimp up their avatars, get personal advantages, purchase virtual land or NFTs. And last not least, they purchase real computers, headsets and other hard- and software to connect to the virtual world. But even though over the past decades all this equipment as well as enabling technologies have developed dramatically, experience regarding the societal and legal pitfalls has been gained comprehensively, and general openness to live in virtual worlds has grown widely, we are still in the creative phase of “imagine all the wonderful things we could do in a metaverse”.

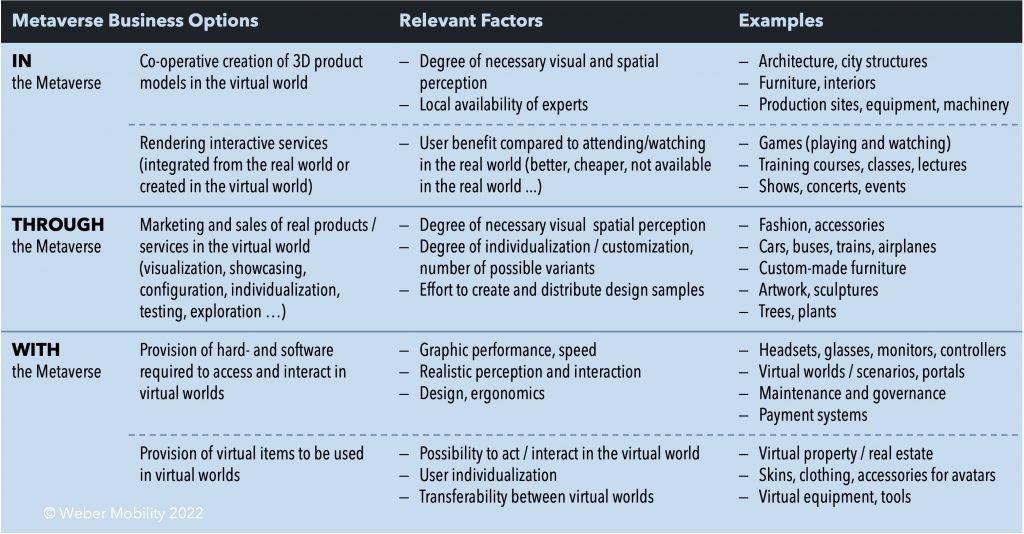

So, what are these wonderful things? Where are the unexploited opportunities of the Metaverse? I would like to structure my personal view on that in three types of business opportunities:

1. Business Opportunities IN the Metaverse: Creating Value in the Virtual World

a) Creating Products in the Metaverse

Probably the biggest potential of a shared virtual space lies in the possibility to effortlessly bring together experts from all over the world to co-operatively build and explore “things” such as buildings and whole cities, furniture and interiors, equipment and machinery – only to name a few options – before they are actually brought to existence in the real world. Picture it like a Teams Meeting where the whiteboard is a 3D space, the tools are not restricted to pens and erasers, and the participants are actually part of this space. The result of this cooperation is a digital model (containing geometrical, technological and other data) that can be exported to the real world where it has a certain value.

From a business point of view, such co-creation in the metaverse makes especially sense if creation and assessment involve a high degree of spatial perception (like buildings, cities or cars and the availability of experts who would be widely distributed in the real world and whose expertise can not be applied through algorithms or AI.

b) Rendering Services in the Metaverse

While the primary value of “things” created in the Metaverse typically lies in the real world, digital services rendered in the Metaverse have their value there: training courses, educational classes, or entertainment like shows, concerts or especially games, offer experiences that can range from similar to the real world (like a concert performed in the virtual space) to impossible in the real world (like most of the co-operative games).

Here, business opportunities arise from charging users for using these services in the Metaverse. And as with all digital artefacts, they can be scaled at no additional costs, too: Hosting an event in the Metaverse, e.g., causes the same effort whether it is attended by ten or ten million people.

Picture 3: Going to the movies in Decentraland 2022

The crucial question however is: What kind of benefit has a customer when attending a metaverse event compared to either attending it in the real world or just passively watching it as a record? If (and only if) interaction with people (via their avatars) and things is significantly better or cheaper or only possible in the virtual world, there will be a market for it.

2. Business Opportunities THROUGH the Metaverse: Marketing and Selling Real World Products and Services in the Virtual World

As a connected 3D space allows the visualization, configuration, and realistic experience of a product and related processes, the Metaverse could be the perfect environment for their marketing.

However, the question to be answered upfront is (again): When does the metaverse have a true customer benefit here – and when is a “normal” website just good enough or maybe even more convenient for the customer to get informed, individually configure a product or look at a product in its intended environment. Is it really necessary or worth to create virtual shopping malls where people’s avatars casually stroll along to enter virtual shops, see virtual products and get greeted by virtual sales clerks (who can be either avatars of real people or bots)?

Even though you can order pizza in Decentraland today: If you are looking, say, for food or smartphones, and especially for goods you have purchased before, a simple online shop with convenient search features will certainly do it. Looking at clothes and accessories worn by your avatar in Metaverse allows a realistic assessment but doesn’t make much sense in immersive mode (as you want to see how you would look like wearing it, not what you would see when wearing it …). Where immersion makes sense is when it comes to spatial perception, e.g., choosing, configuring, and experiencing an apartment, furniture, decoration – or a car – before buying or renting it.

Picture 4: Pizza Shop in Samsung’s Decentraland Virtual Experience Center 837X 2022

And if eventually a metaverse happens to be a promising marketing and sales channel for your product or service, another question arises: Will you create additional business here, or just take existing business from other channels.

3. Business Opportunities WITH the Metaverse: Creating and Selling Hard- and Software to Access and Interact with the Virtual World

a) Provide Hard- and Software to Access the Metaverse

In order to step into the virtual world and interact there with things and other people, headsets and controllers are required. The visualization quality, accuracy, and speed has dramatically improved over the years.

Last not least, the shared virtual space itself must be provided as a cloud solution, including vast business potentials for maintenance and governance services. The more metaverses exist and are populated, the more demand will be there for service providers ensuring technically and socially hassle-free virtual living.

Picture 5: Oculus Quest 2 Headset and Controller (Source Meta)

b) Provide Virtual Items for the Metaverse

A way of doing business already common in cooperative games is creating and selling (digital) products useful or desirable for the users: Special skins, clothing, or equipment for avatars or pre-designed components for products as mentioned under 1) can only be used in the virtual world and not be transferred back in the real world. Just like with digital services, these digital products can be copied as often as you like.

Conclusion:

I would primarily confirm the potential for marketing and sales of real goods in the metaverse. But visualization, testing, or configuration only makes sense for products and services for which the improved spatial perception offers a real advantage over traditional digital channels. Secondly – and independent from what will actually happen there: The provision, maintenance, and governance of metaverses yield surely the most stable and reliable business opportunities in this context.

Picture 6: Overview of Business Opportunities in the Metaverse