.. but you still have such a weird feeling that your future son-in-law says his job is being a blogger.

… but you still don’t believe anyone can make real money from playing computer games.

… but you don’t understand how digitalization could ever change your customers’ expectations.

… but you wonder why the brand you successfully established twenty years ago suddenly has competitors you didn’t even know last year.

… but you still expect your employees to always do their jobs perfectly.

… but you still feel somehow intellectually superior when you scroll through your printed daily newspaper in the morning.

… but you still want to keep your CD collection.

… but you still think your kids can’t hurt themselves on the internet.

… but you still wonder how the formerly isolated madmen suddenly all come together.

Are we really as digital as we think?

Of course, we all feel like we are at the forefront of the digital transformation: we don’t write letters anymore, we chat on WhatsApp instead of making phone calls, we no longer go to the department store but order online from Amazon, book parking and bus tickets with our smartphone, pay casually with our AppleWatch at the supermarket checkout, and, thanks to Netflix, now hardly need grandparents’ TV programs.

In job and education, Covid 19 has led us to be able to conduct business meetings, lectures and school lessons almost confidently online (even if the latter certainly still have some catching up to do here). And some people are already analyzing their production and sales data with AI tools and thus get new and often surprising insights.

Nevertheless, the question remains: have we really understood what the current digital transformation means? How does it differ from the digitalization of recent decades, what opportunities and risks does it entail? But also: what cultural and social change does it bring? And are we prepared to join these changes, or are we not secretly trying to at least partially maintain the status quo we are so familiar with?

What is so different now?

is the transformation of existing products and processes through digital technologies – across industry, business, politics and society – which can range from their simpler application to the enrichment of content and functions to their complete replacement by radically new solutions.

In retrospect, the creation and editing of texts, tables, images, drawings, music and videos on computers can be seen as the first stage of digitization. The worldwide connection of these computers, first stationary, then also mobile, represents stage two and three of digitization and has led to completely new dimensions in communication and cooperation. As a fourth stage, the landslide-spreading of smartphones has not only led to their users being able to access the internet anytime, anywhere; above all, they have enabled behavioural and location-related offers through their cameras, microphones and position sensors and the mass upload of the data generated by them.

Each of these stages has not only produced new solutions and new players, but has also heralded the end of many long-established products, companies and professions. Victims of the first stage include, for example, the manufacturers of cameras, tapes, typewriters or anything necessary for technical drawing. The second and third stages have severely restricted conventional postal services, faxes or long-distance calls, completely abolished services such as telex and rendered data carriers such as floppy disks, CDs or DVDs superfluous. Stage four has dug the water out of many conventional service providers via Location Based Services, such as the taxi companies through app-based ride-hailing services.

The fifth stage we are currently in (which does not mean at all that the previous stages would be even halfway completed) is technically defined by the ability to collect and structure huge amounts of data continuously provided by the growing number of computers, smartphones, connected vehicles and other things (so-called “big data”) and then analyze it with the help of AI-based analytics tools to come up with valuable information: What conditions really depend on whether a particular product is purchased? Which functions of a vehicle are actually used most often – and which are not? Which content of a website is attractive and leads to online purchase – and which ones are not? On the one hand, customer- and requirement-based offers can be derived from such analyses (such as the well-known “customers who have purchased product X have also purchased products Y and Z”); on the other hand, advanced analytics tools make it possible to predict the behavior of people and technical systems with ever greater accuracy. This applies to the experience-based forecasting of traffic jams, maintenance requirements of networked machines, plants or vehicles, or even of human misconduct. In medicine, data analysis supports the early identification of diseases, in finance the prediction of market or price movements. And some online retailers even claim that they can not only predict their customers’ future needs by analyzing their buying behavior, but also, for example, predict a divorce by comparing behavioral patterns, before the parties have even made the decision.

In addition to all these technical possibilities, however, digitalization also brings with it a significant social change, especially at this current stage: the growth of a “digital culture”, the work and lifestyle of a generation that has grown up with digitization (as well as some older people who have adopted this style) and which differs significantly from the usual – as the following examples are to illustrate . :

- Low product and brand loyalty. Those who buy quickly with “one click in” are also gone with “one click out” just as quickly. Loyalty is not expected to be rewarded. New entrants to the market are viewed with interest and enthusiasm rather than with scepticism and doubts about quality and reliability. This also applies to loyalty to their employer.

- Broad level of information: Customers are not only fully informed about the products and services they are interested in, but also about their suppliers. Often no purchase advice is required, because the customer has informed himself so well in advance that he knows more about the product in question than the seller. Digitals are value-oriented, bright, and sensitive: those who are associated with the exploitation of local workers or the cause of environmental damage in internet forums are quickly out of the running despite having attractive offers.

- Feedback culture: Digitals are used to getting and giving feedback quickly and easily. A like here, three out of five stars there. The fact that the experiences of a dissatisfied customer are published in internet forums and networks around the world just minutes later, and how best to govern such cases, is still new territory for many established companies.

- Transparency: Those who want to use digital data should not hope for their quick approval, but should clearly highlight the added value they gain from the transfer of their data. In the same way, if you want to lead digitals as their manager, you should express your expectations clearly and stick to agreements.

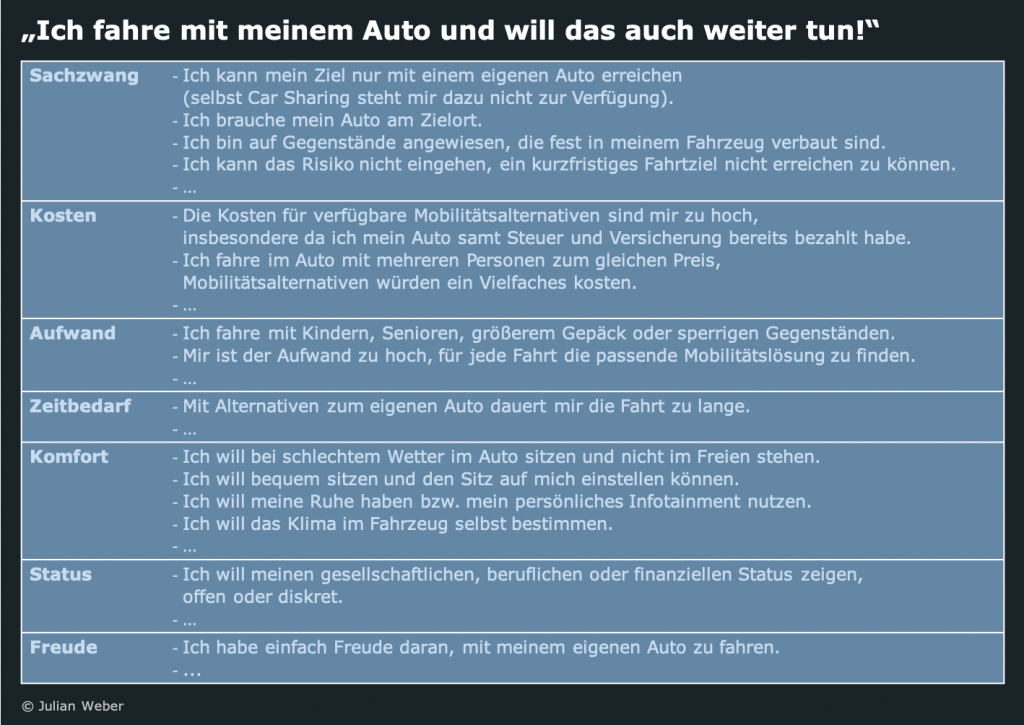

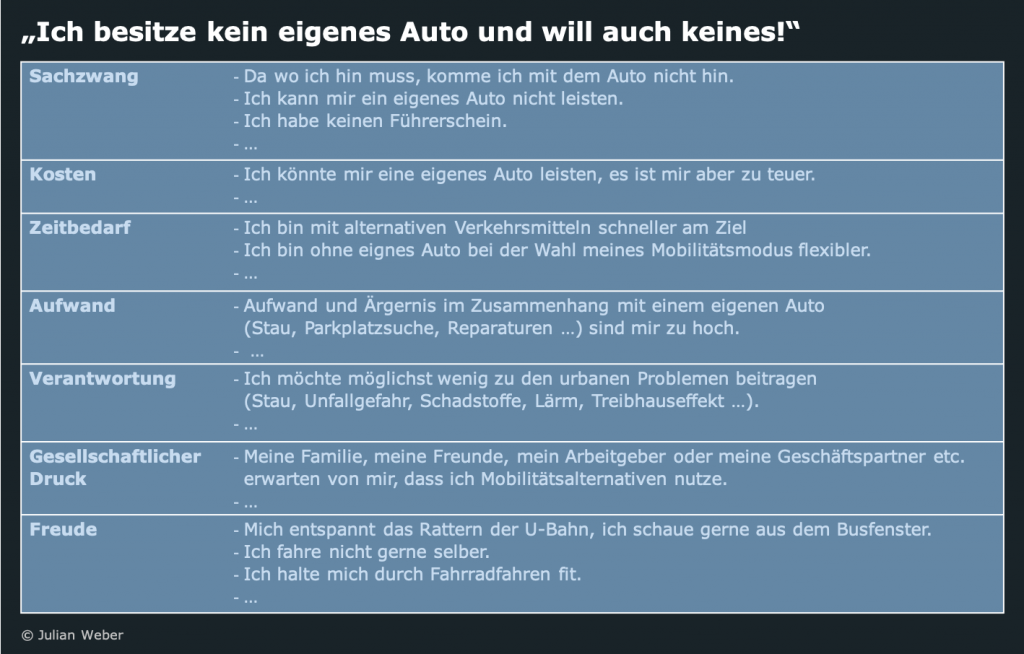

- Benefits instead of owning: Those who have grown up with streaming services instead of their own CD or DVD collection also have less need to own things like tools, cars or bicycles. Digitals are much more receptive to all types of “X as a Service”.

Why is this so relevant for companies: because they are confronted with these digitals in four different ways today: as enlightened customers of their products and services, as sophisticated and not unrestrictedly loyal employees and executives, as factual politicians and legislators who set the legal framework for digital products and processes, and last but not least as critical and rather thematic than partisan voters of these politicians. Dealing intensively with the content and impact of digital culture is therefore a strategic must for companies.

What are the opportunities, risks and changes?

The ability to predict the behaviour of people and systems obviously offers a variety of entrepreneurial opportunities: those who know exactly what the market wants, how their products are actually used and what condition they are in, and thus can offer their customers individual service and product offerings, are not only clearly at an advantage of competition, but can also be able to improve their entire value creation process from development to production and distribution to service and recycling, and thus plan and deploy their capacities in a much more effective and efficient manner:

- Targeted product management including individual product and service offerings

- Design to factual requirements (no over- or under-dimensioning)

- Early detection of design and production defects

- Individual forecasting of maintenance requirements

- Detection of repair needs

- Managed return / recycling procedures at the end of life

Precisely because this increases the attractiveness of the offers for customers so enormously, competitors who fail to enter these technologies and exploit their potential will lose touch relatively quickly. One aspect often overlooked in the euphoria about the obvious opportunities, which can not only slow down the desired digital transformation in the company, but in fact stop it, is the corporate and management culture. While digital change is already relatively broadly anchored in society, executives and employees of established companies often still struggle with it. The use of big data and AI and the associated digital transformation are seen in part as a massive threat to their often laboriously worked-out role and importance in the company, with three aspects of fear in the foreground:

- Devaluation of personal success: Many executives and specialists see the established – and indeed successful – products, processes and procedures of the past as a one of the main reasons for their personal success, and possible changes as an attempt to devalue them, as well as a betrayal of their own values.

- Loss of “dominance knowledge”: The basis for the use of big data and analytics in the enterprise is the merging of all available data into a data lake or digital twin accessible to all parties. But it is precisely this disclosure that is seen as a danger. “Only my department and I determine the exact sales figures. If you want to know how many of which products were sold in which markets, you have to come to me and ask me to do so. I will certainly not make that data available to everyone now. In addition, our mistakes would be immediately transparent to everyone.”

- Rationalization of one’s own workplace: As in manufacturing through automation, the use of big data and analytics also eliminates the need for jobs in other areas – but here those of specialists and executives. The assessment and forecasting of sales or usage data, for example, has long been the responsibility of highly specialized and highly regarded departments in the companies, whose expertise can now be increasingly replaced by powerful analytics tools – which also generate the required forecasts at the touch of a button, at any time and in a comprehensible manner.

What to do?

If the digital transformation is to be successful in the long term, it must never be limited to the introduction of advanced IT technologies, but must also drive forward the necessary change of internal processes and corporate culture in the sense of a change program prescribed and demonstrated by the companies upper management. This includes creating understanding and perspectives, and supporting the personal change of each person concerned individually through qualification. However, this also includes consistently dealing with those managers who are closing themselves off from change for personal reasons and thus ultimately fail to take the decisions necessary for change and the long-term maintenance of competitiveness.