Mobility moves emotions too

A look at the comments on corresponding posts on LinkedIn or elsewhere proves: The change in mobility affects each individual very directly – and is accordingly emotionally documented. Comparable to issues such as nuclear energy or migration applies: anyone who takes a different opinion from myself and that opinion – whether actually or only assumed – threatens my own circumstances, attacks me personally, and I shoot back accordingly quickly and sharply. A factual debate often falls by the wayside.

It is obvious that the right solution for everyone does not exist, indeed cannot exist. In terms of mobility, it not only has everyone’s own individual preferences and priorities, but also everyone has to cope with their own framework of individual and general constraints – be it the personal life situation including the available financial resources, the local availability of certain mobility offers, including the necessary infrastructure or the applicable legal situation.

So anyone who asks the family man, who on the daily commute from his home with garage in a quiet community to his workplace in the nearby business park never had to stand in a traffic jam let alone worrying about a parking space, to think about giving up his car, will hardly find any understanding. Conversely, if you live in the city centre, where the monthly parking space rental in an underground car park is in the range of the leasing rate of a mid-size car, and you come to the office from your apartment in less than 15 minutes by subway, you are probably glad not to have your own car and to be able to use alternatives such as car sharing or ride hailing if necessary.

Change, yes, of course. But where to where?

It is undisputed that driving your own car has been the standard in mobility for decades, and accordingly all other forms of transport have been referred to as mobility alternatives – despite the fact that some of these alternatives have been available for much longer and are also used by far more people than owned cars, especially in the big cities. The fact is, however, that the traffic situation resulting from this standard in the cities is perceived by the people living there – both by motorists and by other road users – more and more as a massive, multidimensional problem: on the one hand, due to traffic jams and parking shortages, on the other hand, by deterioration of air quality, increasing emissions of greenhouse gases and noise, deterioration of road safety and occupancy of the scarcer public space. The fact that more and more people want to move to the suburbs and want to be mobile there with their own car is constantly exacerbating the situation.

All those affected agree that the traffic situation needs to change. However, opinions differ clearly on how the problems could actually be solved and how a corresponding change should look like: those who want to continue driving hope for more roads and parking facilities, whether by expanding the existing transport infrastructure or by switching to mobility alternatives as possible. If you care about reducing emissions, you want the continuous replacement of internal combustion engines by electric drives. And if you want to have more green spaces and space for alternative mobility in your area, you might want inner cities without private cars.

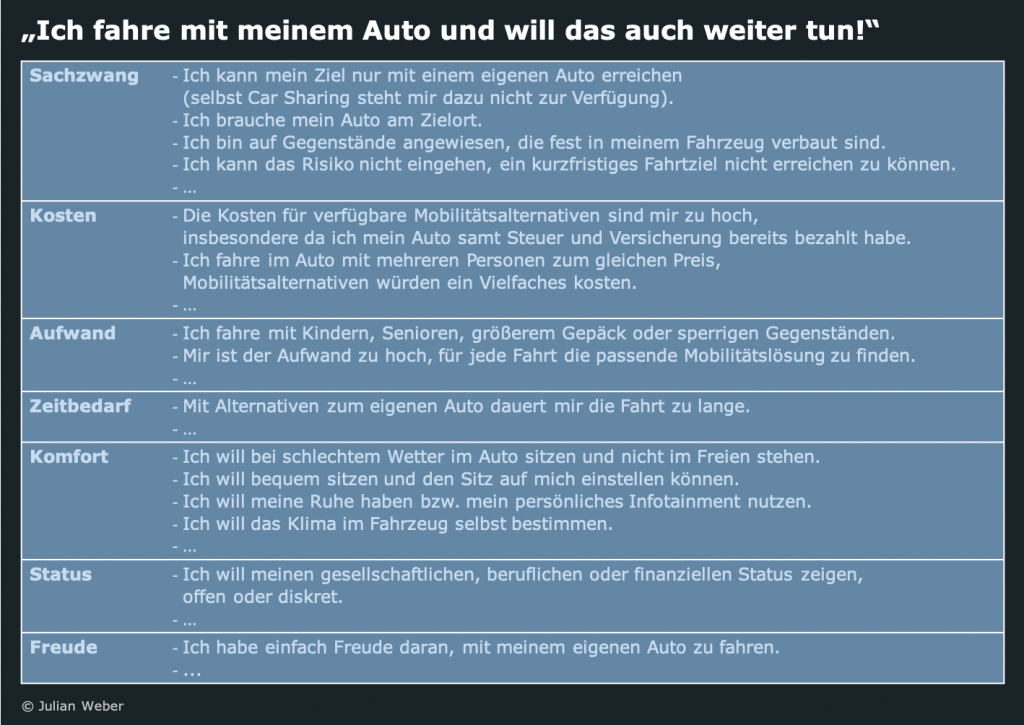

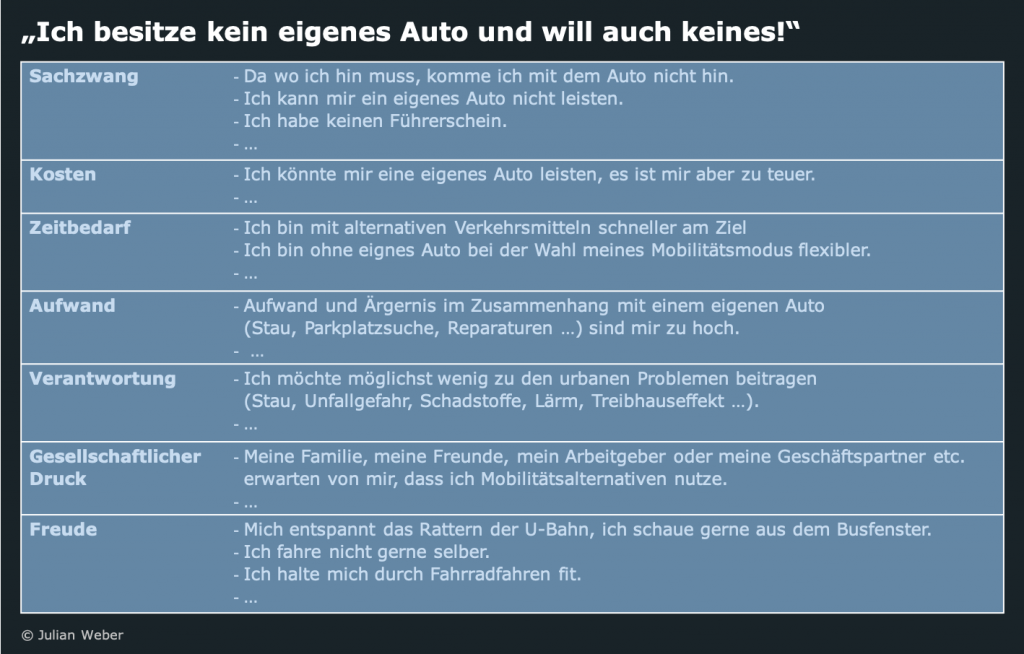

Extreme positions of individual mobility

In the end, the real mobility situation is always the result of the sum of individual decisions made within a framework of personal possibilities and preferences, market-side offers, available infrastructure and last but not least regulatory/political conditions. The individual not only decides on his or her personal mobility mode, but also regulates the supply of mobility products and services via demand and also influences the promotion or rejection of different solutions by means of regulatory requirements through the election of a party or a delegate. The change in mobility is thus supported, at least in democratic conditions, directly and indirectly by the will of the majority – and is therefore often difficult for the individual to understand and endure.

In this situation, on the one hand, many people today have the impression that politics and society are interfering in more and more things that used to be a purely private matter. Of course, everyone is allowed to smoke – but not everywhere for a long time. Of course, everyone is allowed to wear whatever they want – but they are also confronted with the conditions under which their garments were made at the other end of the world. In principle, everyone is allowed to eat what they want – but they have to accept questions about fair trade, environmental protection and animal welfare. The same feeling now arises in terms of mobility: Can I not even drive a car now?

On the other hand, there are people with different personal values and priorities who, for example, attach great importance to ecologically and socially sustainable life and action, cope wonderfully without a car of their own and feel affected by the mobility behaviour of others in their quality of life. From such a point of view, it is often incomprehensible why someone wants to hold on to their own car around everything in the world.

How do we get to sensible and majority-capable solutions here as citizens with mobility needs, as mobility providers or even as politicians, despite all differences of opinion? An indispensable prerequisite for this is the fundamental assumption that people with an opinion other than their own do not generally represent them out of stupidity or malice, and the willingness to deal with conflicting points of view in a factual and differentiated way in a consideration of the overall system. A look at the motives from which extreme positions are represented helps. In this sense, figures 1 and 2 show different reasons, for which the positions “I drive with my own car and want to continue doing so!” and “I don’t own my own car and don’t want one!” are taken – each descendingly ordered by how easy alternative can be found.

In addition to the understanding of the “opposite side”‘s reasoning, this analytical analysis also reveals the shortcomings of one’s own reasoning or supply: those who want to sell cars would do well to understand why some people do not or no longer address this offer, and with which vehicles or services customers could be held or recovered. Those who offer alternatives to owned cars, on the other hand, should look very carefully at what drives people to continue to drive their own cars in spite of everything.

Let us not be under any illusions: in the end, this approach will not lead to a result that everyone is happy with. But it makes the debates on mobility change noticeably more constructive and thus leads it clearly towards an overall optimum.