#emobility

Whether eagerly yearned for or grudgingly conceded: By now, you have probably accepted that electric cars are inexorably on the rise. And even though you are sure that at least in some places there will still be cars with combustion engines on the road by 2050, it surely looks like EVs and Plug-in Hybrids will prevail in the cities. However, what you still find far less clear – even though you witness more and more public chargers around – is how EV drivers will be able to cope with the limited range of their vehicles in connection with the perceived scarcity of charging stations. And while at the same time some nerdish engineers reiteratively broadcast that fuel cells and hydrogen will solve this problem for ever, you still cannot get rid of this uneasy mental image of a huge crater stretching over a highway after a car crash with a poorly maintained hydrogen vehicle involved.

#mobilityservices

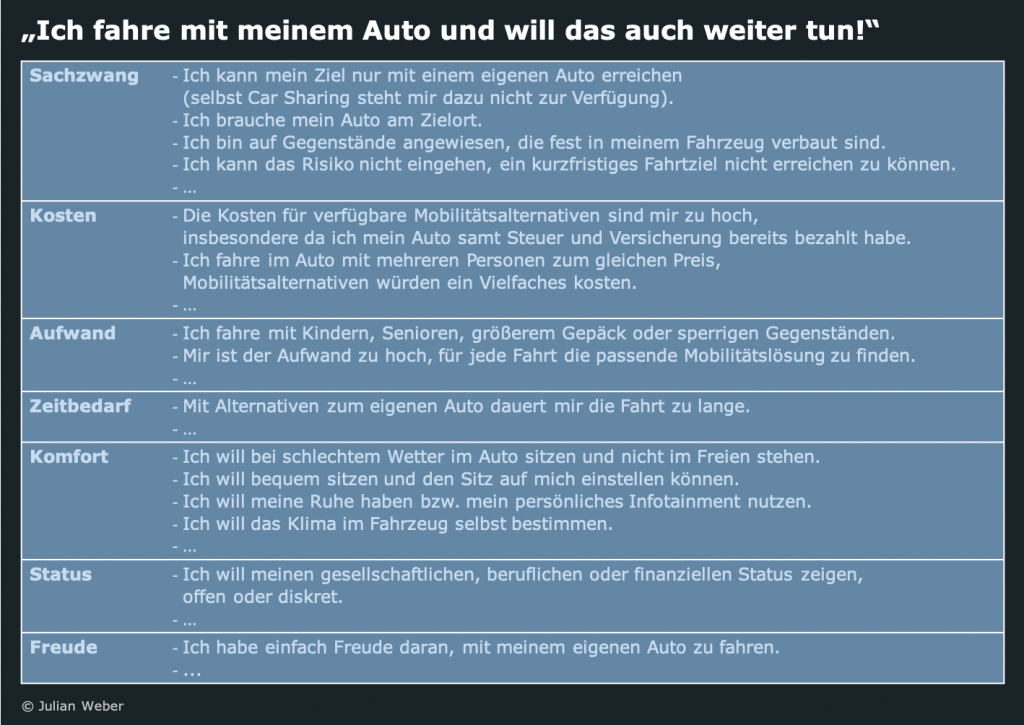

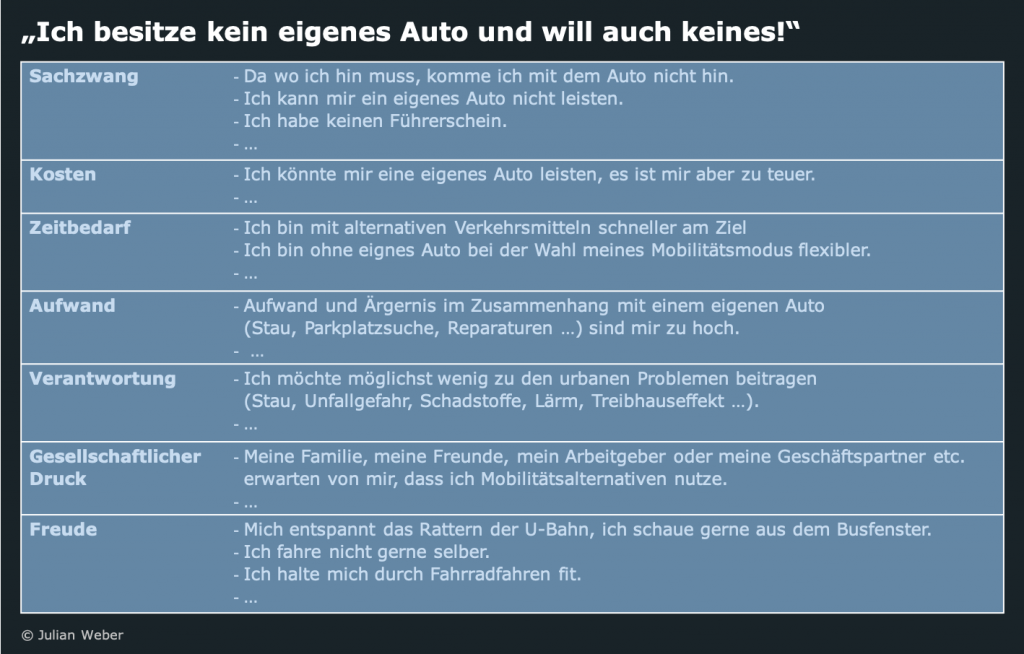

Then, as you read through your business strategy journals, you are told over and over that car ownership, the century old mobility pattern number one, is in rapid retreat. Urban teenagers, whose fathers were dreaming of fancy sports cars when they were their age, don’t even go for a driver’s license anymore. If train, bus or bicycle is not an option, people would not buy or lease cars but rather share a car or call a ride hailing service like Uber, the affordable and app-steered successor of what has long time been known as a taxi. But what is worrying you even more is that new digital service providers are said to take over the complete mobility business soon, with automakers being downgraded to basic hardware providers and public transport companies begging for contracts.

#autonomous

On top of that, automakers claim they will soon bring autonomous vehicles on the road. Not just something like an extra-advanced driver assistance system, but cars with neither steering wheel nor pedals but lots of extremely expensive sensors and software that must be extensively tested and meet standards initially developed for military aircraft. And while in spite of all confidence in engineering you still wonder how these cars would ever make it safely through unsecured road works or snowstorms and – even more significant – who apart from ride hailing providers would actually want to buy them, you witness the heralded date from which on these robocars should populate our cities’ streets being postponed year by year.

#digitalization

And as if all this wasn’t bad enough, some of the young guys around you, the ones wearing sneakers, a full beard and watching e-sports, tell you that data is the new gold, that big data means even more gold, and that your company should work agile, fail fast, provide something you would call completely unacceptable but they call minimum viable product, scale and ultimately indulge yourself in a so called digital transformation. All that of course independently from whether you are in automotive, mobility services, energy, public transport, insurance, law, or whatever. After thinking it over, you are left with the feeling that this is not all new but still kind of frightening. If only you would understand all these fancy IT buzzwords.

#change

If your work was related to mobility for the last couple of years, all of the above probably sounds familiar. The battle-hardened manager, now somewhat disoriented and undetermined in this overgrown jungle called mobility of the future. How do all these bits and pieces fit together? The good news is: No one has ever been brought from one place to another by software alone. But the fact that vehicles and smartphones send and receive an exponentially increasing amount of data, that they are connected to back-end servers and with each other, and that artificial intelligence can create astonishing and valuable information from this data, will not only improve vehicle and service functionalities but dramatically change the way they are developed, produced or rendered, marketed and sold – and especially how vehicles and their private or corporate customers are served after sales.

The key for survival and success is embracing change. At the end of the day, the question is neither if you should proactively engage in a digital transformation nor when you should do it (the answers are yes and now). The sole question is how – and can usually not be answered sufficiently by the people who brought your company to where it is today …

First published on LinkedIn on 5. August 2020